“In order to perpetuate itself, every oppression must corrupt or distort those various sources of power within the culture of the oppressed that can provide energy for change.” — Audre Lorde

In a recent conversation, I found myself defending the spiritual traditions of the Akan against one of its descendants, who, now spiritualized in and by the West, harbors that familiar yet loathsome contempt many Africans still feel towards the spiritual traditions of their people.

I am a Nigerian woman who has lived with and embraced alternative spiritual beliefs in a country that is almost evenly split between Christianity and Islam. The casual disdain many Nigerians show towards African spiritual traditions, due to their upbringing in either the Church or the Mosque, is not new. Until proven otherwise, I have come to expect this disdain and, consequently, the dismissal of African spirituality from Nigerians and other Africans.

Yet, even though this disdain no longer shocks me, it still manages to surprise. Like when a Nigerian global superstar dismissed the spiritual culture of her ancestors and clung firmly, and rather ironically, to the spiritual beliefs of another people. Or when my Akan counterpart, a rather queer individual, casually demonized the water spirits of her ancestral land.

These dismissals are surprising and reflect a self-denial that was externally imposed by the colonial machine and is now perpetuated by the colonized. What are the consequences of this ongoing self-denial? Who benefits when Africans and other colonized peoples worldwide continue to self-abnegate?

Since the pandemic shattered our collective illusion about the world we live in, it has become even clearer and easier to see how the hetero-patriarchal-capitalistic world we have created is unsustainable for our survival now, let alone for future generations. Movements have sprung up across all corners of the globe demanding a shift from these oppressive and anti-life ways of being. Over the last year, nearly two years, we have witnessed a concerted global effort to draw attention to the atrocities in Palestine, a movement that has rippled through and is bringing awareness to injustices in other places like the Congo, Sudan, West Papua, and so on.

The world is awakening to the lies that the West has told for eons, and humans are demanding external change. This is positive; it signifies progress for the species. However, our push for change should not begin and end with external ways of survival. The emphasis on the external and material aspects of existence is part of the deception we have been sold. It has necessitated a focus on material gains and excessive consumption at the expense of the individual and collective human spirit.

The word ‘spirit’ comes from the mid-13th century, meaning: “life, the animating or vital principle in man and animals.”

Spirit also has the following derivatives, “spirit, soul” (12c., Modern French esprit) and derives directly from Latin spiritus “a breathing (of respiration, also of the wind), breath;” also “breath of a god,” hence “inspiration; breath of life,” hence life itself.”

A disconnection from the spirit means a disconnection from life itself, and we wonder why we live in an anti-life world. No person or people disconnected from their spirit can make sense of life or find any true joy or meaning because they are essentially separated from the spring (Spirit), which is the source of all things. Thus, it becomes easier for such people to become agents of destruction or be easily destroyed.

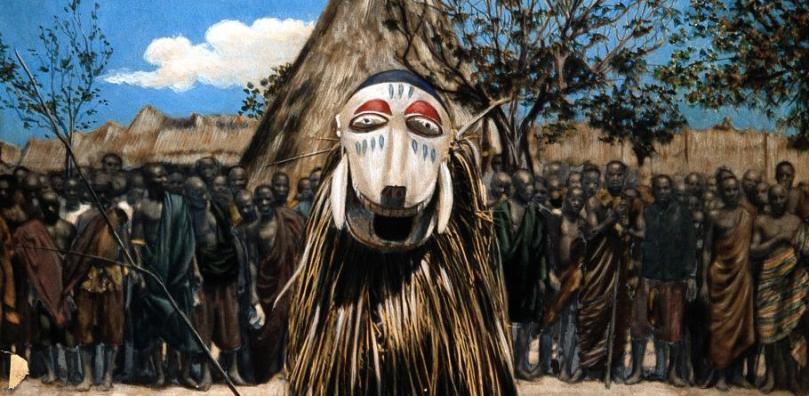

The myths and Spirits of indigenous cultures nourished life in the people and imparted a sense of meaning that has since been lost and, in many cases, replaced by the spiritual beliefs of a more dominant culture. Many Nigerians who are now Christian or Muslim have embraced these spiritual traditions at the expense of their ancestral beliefs. Even though history is visible to all, we often pretend that many of these conversions did not occur violently.

Perhaps denying the violence that led to the loss of our spirits is necessary for our survival, but I find that the question remains: who benefits from our self-abnegation? What systems—spiritual, economic, agricultural, etc.—thrive when we continue to either willingly, passively, or unknowingly reject ourselves?

This brings us to the opening quote: To perpetuate itself, every oppression must corrupt or distort those various sources of power within the culture of the oppressed that can provide energy for change.

For the colonial machine to establish itself, it had to strip indigenous people of their sources of power. For the colonized, this meant the destruction and distortion of all systems and practices that connected them to an idea of God or the Great Spirit, as many traditions called it, who is the source of life and, therefore, power.

In a world where injustices are apparent and the fight against them shapes how many of us live our lives, it is crucial to make a connection between the state of the world and the separation from Spirit//God. As stated earlier, this separation necessitates our fixation with the physical and everything that concerns it.

Yet, Spirit can only be ignored for so long before it demands a reckoning.

To emphasize this point, let’s recall the beliefs of the Mawri in Niger, who explained this essential connection to the spirit through the belief that each human is born a twin. One twin is bound to the human world of existence, while the other is bound to the spirit world. It is the responsibility, then, of humans to nurture the connection with their spirit sibling; otherwise, they would have a difficult life.

The story captures the current state of human existence. We have, for so long, lived as if separate from our individual and collective spirits, and now we are all feeling the pain of that separation. The degree of the pain felt is proportional to how far a person, group, or society has strayed away from their Spirits, but there is no mistaking it: we are living in difficult times, a situation only worsened by the fact that many of us refuse to recognize that our true source of power is not anything that can be seen, touched, or felt in the material.

We are now doing the colonizers’ work for them by refusing to see that we were a complete people with cosmologies, ontologies, and views of the world that shaped our lives and thus gave them meaning before the trauma of colonization fractured our identities. The work of decolonization, which I argue should be termed ‘reindigenization,’ can never be complete without addressing and tackling this crucial separation between the colonized and their Spirits.

If our Spirits animate life, give it meaning, and are the breath of God within us, and thus life itself, then the separation between the colonized and their spirits has created zombie-like people who are alive and animated but lack the crucial vital energy that infuses life and gives it any meaning. As such, our efforts to ‘decolonize,’ perhaps also lacking the true essence of Spirit, will only bring us so far.

We will never know true freedom until we remember who we are, and we will never remember who we are if we continue to reject our Spirits because we learned long ago that only the spirits of our oppressors are good, even when they tortured us to drive the point home.