My name is Martha Laraba Sambe. Before any titles or identities—those I claim for myself or those others may assign—the most important truth about me is that I am human, and this is the same for each of us here today; we are human, first and foremost.

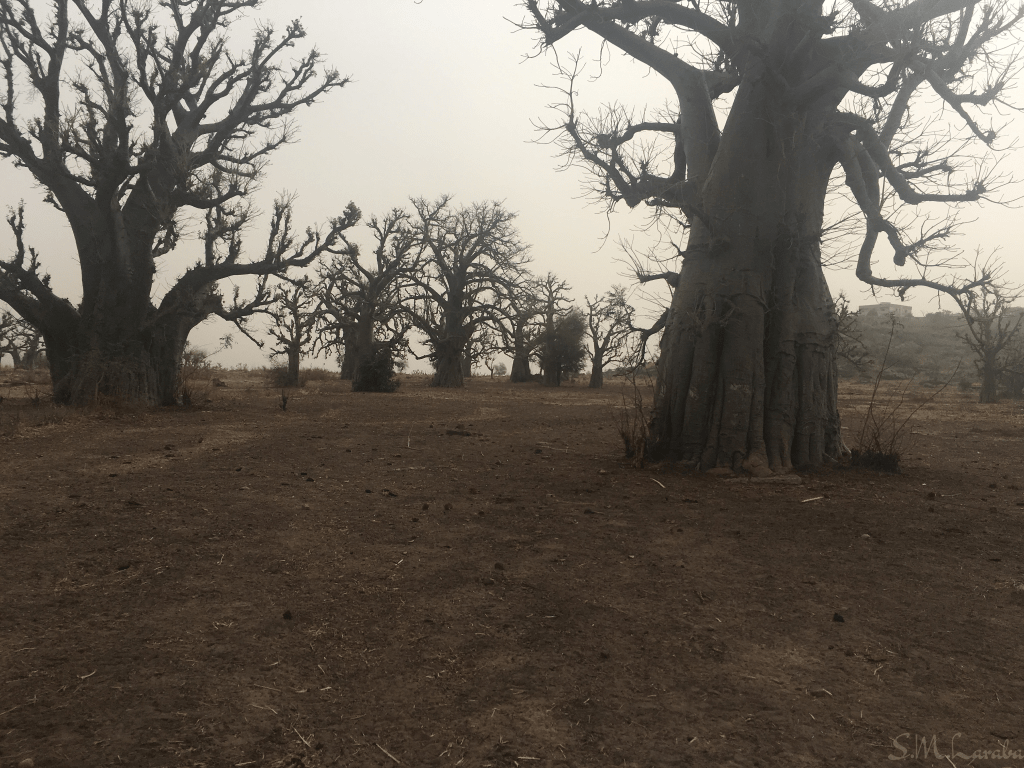

I begin by expressing my sincere gratitude to everyone who made it possible for me to speak here today: the organizers, volunteers, funders, donors, and this remarkable museum, whose open doors welcome us all. It is a profound honor to stand within an institution that houses artifacts from my home country, Nigeria. I pay respect to the ancestors, lineages, and nations from which these treasures originated. In the spirit of Ubuntu, I recognize that our gathering today is possible because of those who came before us, the ancestors whose lives were fundamentally changed by Western imperialism.

I stand here to reclaim my ancestors’ time, to give voice to their silenced stories, and to demonstrate the meaning of resilience in the face of forces that have sought to dominate and erase our existence. If my words appear critical, it is because I carry the pain and anger not only of my own people, but also of many nations that have been pillaged across Africa and the world. Nevertheless, even as I speak from this place of pain, I commit to speaking with care, as nothing built solely on anger and pain can endure.

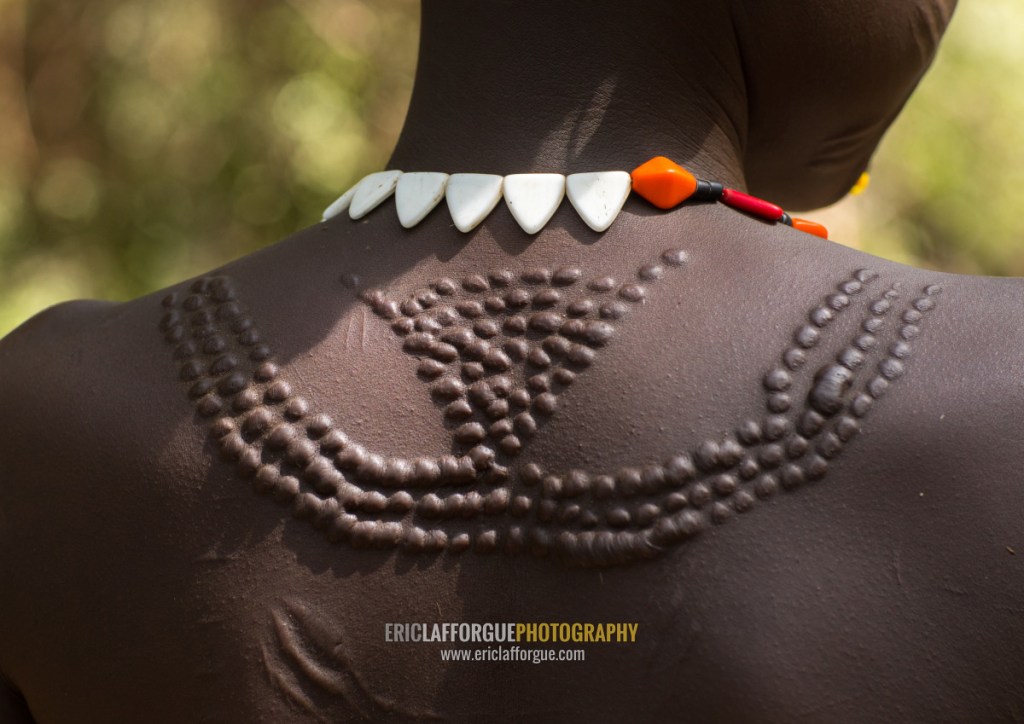

The history of Western imperialism is not a distant past; it remains an ongoing reality that shapes and influences every aspect of our lives. The theft of cultural artifacts was not merely about ownership, but about power—the right of colonized peoples to tell our own stories, to define and understand ourselves, our value systems, and the heritages that shaped our ancestral communities. The loss of these artifacts represents a rupture in the continuum of collective memory, pride, and shared identity among many Indigenous peoples.

Yet, we are not solely defined by what was taken from us. We are also defined by what we have preserved, even under the persistent and oppressive gaze of imperialism. Our ancestors found strength in community while honoring the wisdom embedded in our traditions, and the unbreakable thread that connects us. The philosophy of Ubuntu, ‘I am because we are,’ continues to affirm this shared connection, reminding us that humanity is intertwined, that healing must be a collective process because our struggles are shared.

The Rise and Demise of Western Imperialism

Right now, we are witnessing the breakdown of systems in the Western world: environmental disasters, deep social inequality, resource shortages, and wars are increasingly prevalent. The Global South faces parallel struggles, including genocides, conflict, climate crises, and social unrest. These are not isolated incidents, but interconnected threads within a broader process of global transformation.

What unites these overlapping crises? What underlying cause connects the challenges experienced by both the West and the Global South?

At the core of these crises is Western imperialism, a force whose legacy extends across continents and centuries. A comprehensive understanding of Western imperialism requires recognizing that it did not emerge independently. Rather, imperial expansion unfolded within a complex, interconnected, and culturally diverse global context. Before European expeditions began in the sixteenth century, international affairs were characterized by multiple centers of influence, resulting in a polycentric distribution of power, knowledge, and cultural development. Civilizations across Africa, Asia, and the Americas flourished, each contributing unique knowledge systems and innovations to the world.

In West Africa, empires such as Benin, Mali, and Songhai prospered through vibrant trans-Saharan trade networks. The city of Timbuktu stood as a beacon of intellectual pursuit, supporting the study of poetry, astronomy, and theology. These were societies of sophistication and depth, with thriving economies and centers of learning. Along the Swahili Coast, cities such as Kilwa and Mombasa engaged in extensive trade with India, Arabia, and China, participating in a widespread Indian Ocean commercial network that stretched from inland Africa to distant shores. Across Asia, China during the Song and early Ming dynasties maintained the largest global economy, introducing innovations such as the compass, paper, and printing. Indian kingdoms influenced international markets for textiles and spices. At the same time, the Islamic world fostered cities like Baghdad and Cairo as prominent centers of scholarship and science, facilitating the translation of Greek philosophy and the advancement of algebra, medicine, and astronomy.

Likewise, in the Americas, civilizations such as the Aztec, Maya, and Inca established sophisticated urban societies rooted in ritual practices, reciprocal relationships, and environmental stewardship. These diverse societies were united by a relational approach to power—where spiritual and political spheres were intertwined, and trade was defined by mutual exchange rather than domination. Across many of these societies, power operated through relational dynamics rather than absolute authority. Spiritual and political spheres were interconnected, and trade was characterized by mutual exchange rather than domination.

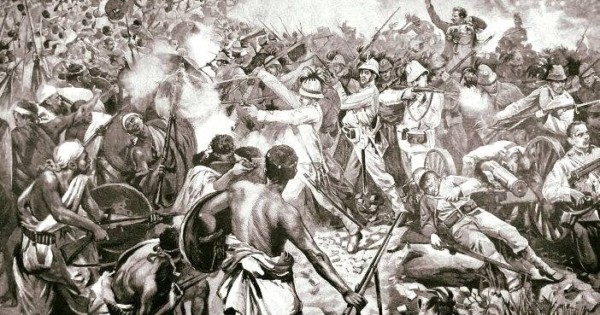

Around 1500, the world experienced significant transformations. Europe, still recovering from plagues and wars, sought new expansion opportunities. Rather than establishing cooperative relationships, European states pursued power and conquest. Through colonization, enslavement, and resource extraction, European powers fundamentally transformed global structures by imposing their socio-political and economic models on diverse societies. This period marked the rise of Western dominance, which was established through exploitation and control rather than mutual benefit.

Between the 1500s and 1800s, Western powers established global dominance primarily through control and force. In the twentieth century, Western dominance reached its apex with the worldwide dissemination of ideas such as capitalism, democracy, and Christianity—systems imposed on societies encountered during Western conquests. Subsequently, these and other Western systems have served as mechanisms for continued control and domination over the non-Western world.

In English, there is a saying that goes: “A house built on shaky foundations cannot stand.” European exploration of the non-Western world was marked by violence and aggression rather than cooperation and benefit, and we are currently witnessing the unraveling of the structures established through conquest and maintained by violence. The foundational elements of Western imperialism, including endless extraction, oppressive hierarchies, and domination over land and life, are collapsing under their own weight as evidenced in accelerating ecological collapse, increasing inequality, political fragmentation, and a litany of violent conflicts across the globe.

The world created by Western domination, no longer able to sustain itself, is gradually imploding, and we are all witnesses. We are witnesses to ecological disasters, multiple genocides, increased polarization, famine, etc., etc. Yet, we are also witnesses to a refusal, across various parts of the globe, to accept systems that treat both humans and the Earth as expendable. And as convoluted as this era is, it does not signify the end of the world, but rather the conclusion of a specific global order. The myth of Western indispensability is diminishing, thus creating space for new possibilities and alternative ways of being.

The Prescient Wisdom of Indigenous Traditions

As we transition from reflecting on the collapse of Western imperial structures to exploring the enduring wisdom of Indigenous and non-Western societies, it is crucial to recognize that the answers to our contemporary crises may not lie in reinventing new systems from scratch. Instead, we can look to longstanding traditions that have withstood centuries of disruption and marginalization. These worldviews, grounded in interdependence and reverence for all life, offer not only a critique of past injustices but pathways for renewal and healing. By turning our attention to these alternative frameworks, we move toward reimagining a future rooted in balance, reciprocity, and collective well-being.

When an established system can no longer accommodate the full range of human potential, it inevitably disintegrates both internally and externally. Mystics refer to this as a “Dark Night of the Soul.” I argue that humanity as a whole is currently in a Dark Night of the Soul, a nebulous transitional phase of moving beyond the era of Western domination and into an uncertain yet open future.

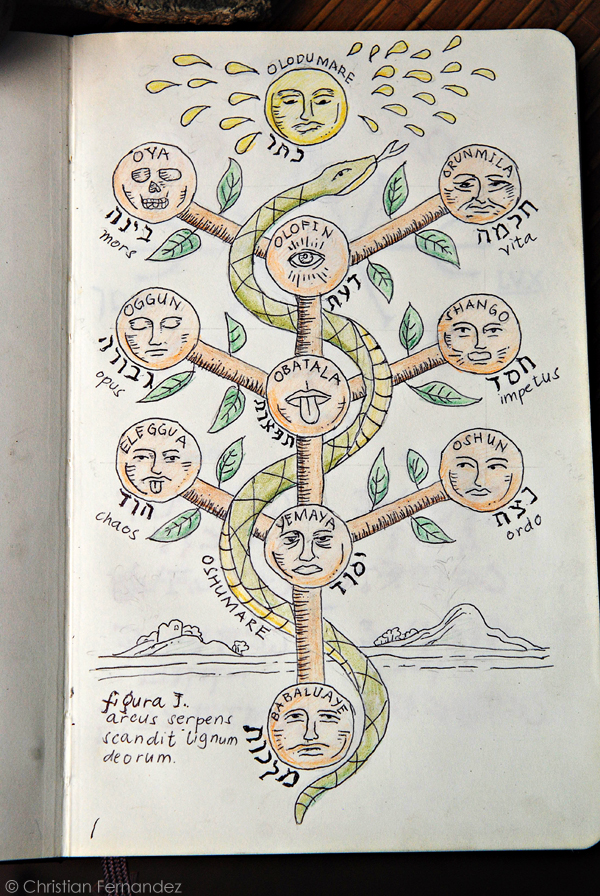

In a previous post, we explored how many African and Indigenous traditions perceive time as cyclical rather than linear. In these worldviews, looking toward the future often means drawing on the past, as the past and future are interconnected within the same temporal framework. Therefore, any effort to envision a world beyond the West, its domination, and the consequences we are experiencing must first seek to understand what preceded it.

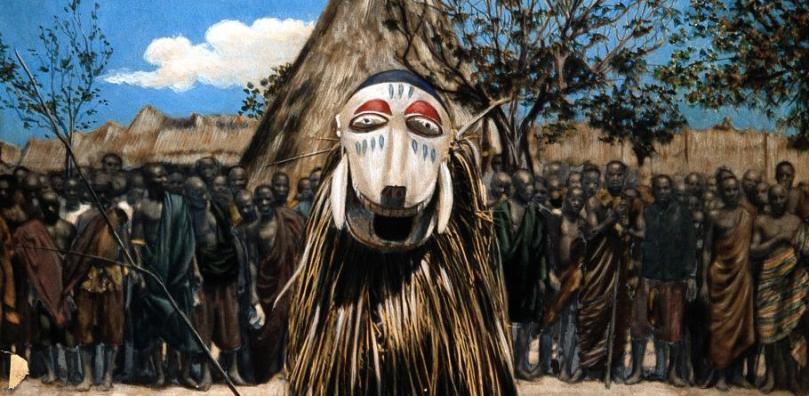

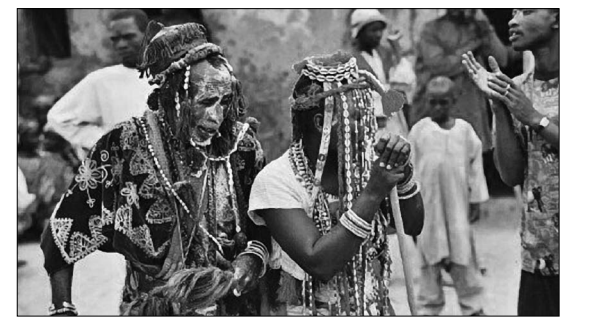

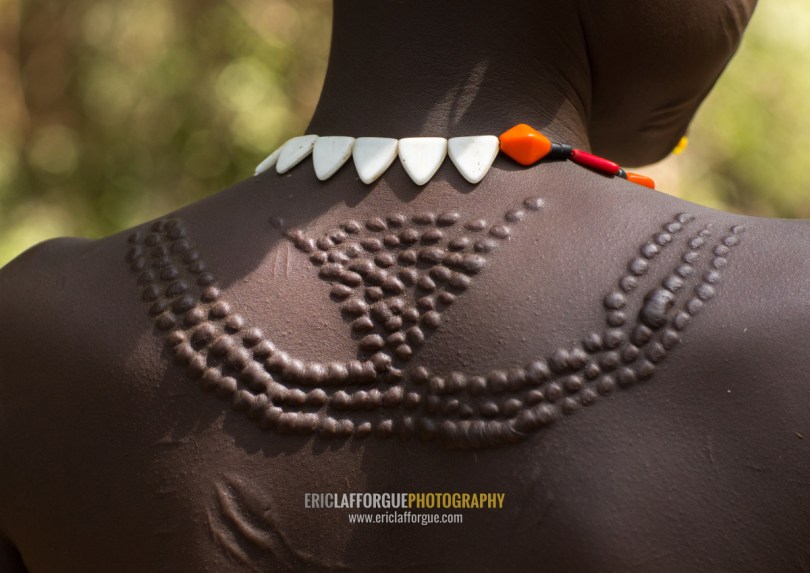

Before Western expansion, global societies possessed—and continue to retain—complex systems of governance, scientific knowledge, spiritual beliefs, and ecological management. Societies across Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific maintain unique cultural practices, yet share core concepts regarding existence and interconnectedness. These indigenous worldviews emphasize relationality, indicating that all beings are interconnected within a shared system of life. This shared concept of relationality, along with other worldviews present in Indigenous and non-Western cultures, is what I refer to as ‘indigenous schemas’.

The following discussion will focus on three principal indigenous schemas, which primarily center on these core ideas:

- The land—our Earth—is a living ancestor, not an object to be bought, sold, or exploited.

- Governance is based on consent, accountability, and community involvement, and knowledge is always shared—passed down through oral stories, rituals, and hands-on experience.

- Economies operate on reciprocity, focusing on fair exchange and the replenishment of used resources.

Western colonizers dismissed Indigenous philosophies as primitive because these ideas fundamentally challenged a worldview rooted in hierarchy, scarcity, and domination. However, Indigenous philosophies across the globe share a foundational principle: The Earth, as all beings in it, is sacred, and each being is an expression of the Divine Spirit and/or Creator. In contrast to Western thought, which positions humans above nature, Indigenous perspectives see humans as one component within a vast, interconnected cosmos. In this perspective, relationships, rather than hierarchies, serve as the main organizing principle.

In indigenous systems, value is not determined by productivity or profit; rather, it is seen as inherent to existence itself. Western colonialism sought to undermine this perspective because domination conflicts with the recognition of the natural world as sacred. Colonial systems initially portrayed land, forests, animals, and entire populations as soulless, justifying their exploitation and dispossession. For this reason, reclaiming the sacredness of all life is not merely an abstract ideal but a concrete, actionable process encompassing socio-political, ecological, and spiritual dimensions. This foundation is essential for societies aiming to achieve sustainability beyond Western paradigms.

Indigenous systems emphasize the sacredness of all life and highlight the interdependence of all living things while respecting each being’s autonomy within the larger whole. In Indigenous societies, the concept of freedom does not mean being separate from others or acting without regard for their well-being. Instead, freedom is evident in how individuals honor their relationships with the community, the land, and their spiritual connections. Each being has a role and corresponding responsibilities that come from belonging to this greater whole. Ultimately, a person’s identity is shaped by their contributions to the community, and power is shared collectively rather than imposed by a single authority.

Western perspectives often define freedom as independence from others. In contrast, Indigenous societies emphasize the interdependence of all living beings and the importance of maintaining balanced relationships with them. This viewpoint highlights that even those we may dislike or disagree with are part of the interconnected web of life, and nurturing balance is essential for both personal and societal well-being. Strength, resilience, and meaning are cultivated through reciprocity—an ongoing exchange of support, knowledge, and care. To move beyond Western notions of autonomy, it is important to embrace interdependence as a form of sovereignty rather than seeing it as a sign of vulnerability.

Within Western capitalist systems, value is extracted from land, labor, and life until resources are depleted. In contrast, Indigenous societies have traditionally operated under economic systems that prioritize giving back to the environment, rather than ceaselessly taking from it. Regenerative economics is based on the belief that the Earth is a living entity, not merely a resource. This economic model also emphasizes the following principles:

- Resources extracted from the environment must be replenished

- Well-being is measured over many generations, and not just by short-term profits

- Wealth is distributed to sustain the community, rather than concentrated to maintain individual or institutional power.

- Growth is signalled by societal wellbeing, nature thriving, and the health of relationships within communities.

These ideas have endured despite colonization because they are rooted in the very logic of nature. Nature functions in cycles, where decay, renewal, giving, and receiving all play vital roles. The environmental and social crises we are currently witnessing suggest that our existing systems are fundamentally misaligned with the laws of nature. There are many lessons to learn from the regenerative economic models of indigenous cultures, which can help the world protect both the environment and society, allowing both to flourish and, importantly, ensuring a sustainable future.

To Decolonize or Not?

Finally, it is important to consider the role of decolonization in shaping contemporary society. I do not fully concur with the mainstream definition of decolonization as “the process of undoing colonialism by ending the domination of one country over another.” Nobody can undo colonization, just like none of us can go back in time to stop Western Imperialists from setting sail to conquer other parts of the world.

So where does that leave us? Should we just give up on “decolonizing”?

Well, yes and no.

I argue that the term “decolonization” deserves reconsideration because it tends to focus on the very concept that needs to be transcended. Additionally, it is crucial to address and repair the extensive harm caused by colonization. In this respect, I differ from many scholars who view decolonization as primarily a governmental or institutional effort. I believe that decolonization should also be understood as an individual endeavor. Fundamental changes in perception and relationships with the world begin in each person’s mind. Everyone is born into and lives under imperialist-colonial systems, and the legacies of these systems continue to shape contemporary life.

The influence of dominant and hierarchical systems is evident in all areas of life, including international and local politics, workplace dynamics, personal friendships, relationships, and even spiritual spaces. These hierarchies shape our perception of human life, suggesting that some lives are more valuable than others. One of the most damaging legacies of the West is its role in teaching us to devalue life to such an extent that it can be easily ignored and destroyed. In Germany and much of the Western world, this devaluation of life continues, particularly in the mainstream and government responses to the genocide of Palestinians following the attacks on October 7, 2023.

This devaluation is particularly evident in the thousands of deaths occurring in Sudan and the Congo, where prolonged conflicts have persisted for decades. However, these countries have not received the same level of media attention or public outcry as the Palestinian crisis. Why do you think this disparity exists? Why do many in the West seem desensitized to the deaths of Black and Brown people around the world? It ultimately comes down to how dominance and hierarchical thinking have shaped our perceptions of the “other” and how those perceptions influence our responses to global events.

When discussing decolonization, it is essential to recognize individual responsibility. Everyone has been socialized within systems that perpetuate hatred and devalue others. Decolonization fundamentally involves unlearning hatred and relearning values such as respect for all life, reciprocity, and stewardship.

In conclusion, the decline of the West does not merely signify the end of a civilization; it represents the end of a particular mode of thought.

- Domination, extraction, and greed have reached their limits and can no longer support life or provide meaning.

- The future must not be shaped by the same logic that created our current unsustainable world order.

Thank you for your attention.

A lecture delivered at the 2025 Fluctoplasma Festival under the Theme “Visions Beyond the West”. Go here for further readings and sources.