October 2020 will be remembered for a long time as a pivotal moment of change in the history of Nigeria. The fact that the country marked the 60th anniversary of its independence in the same month is perhaps a mere coincidence with the uprising that occurred days later. Though an intimation with the nature of colonial trauma, the inherited vestiges of disdain and disregard for African lives that police brutality and other malaise signify, instruct us that perhaps the 60th independence of Nigeria was in fact a catalyst for the uprising.

Whichever way you look at it though, no one could have anticipated that it was at this important point in the history of Nigeria that Nigerian youths would rise in unprecedented numbers to demand an end to years of police brutality, as well as accountability from leaders, and a truer and more creatively imagined independence from a colonial hierarchy of being.

The resistance in Nigeria is one of many that have occurred across the continent in the year 2020, even though the world had been brought to its knees by a pandemic. In South Africa alone, a total of 511 protests were recorded from 27 March to 31 July 2020. Namibians, particularly women, were also out on the streets in the same period as the Nigerian protests demanding an end to widespread gender-based violence. Meanwhile, in Mali, we saw thousands march in the street to demand an end to poor leadership.

The year 1960 is referred to as The Year of Africa because, in that year, at least 17 African nations became independent from their colonial rulers. These countries all have interesting stories about the movements, and in many cases, the resistances, that led to their independence and the fact that a wave of movements and resistances are being witnessed exactly 60 years later can seem to be more than a coincidence. Social resistance is nothing new in Africa, however, the fact that we have better tools to organize, report, fundraise and support each other across borders and physical barriers, is perhaps what has made some of these movements as monumental as they have ever been.

In keeping with the theme of resistance, this piece takes a look at how elements of two African belief systems influenced two major social resistance movements in colonial Africa.

The Chimurenga Resistance (Zimbabwe, 1896-1897)

In any social movement, religion can either be a catalyst or an inhibitor. These roles are represented by Max Weber’s notion of a “proactive religion” which can lead to socio-economic transformation; and Karl Marx’s notion of a passive religion, where he famously describes it as the “opium of the people” and consequently incapable of bringing about any kind of social change within oppressive systems.

The story of the Chimurenga Resistance exemplifies how religion and religious elements can serve as catalysts for social change. Chimurenga is attributed to the Shona people and can be translated as “revolutionary struggle” or “uprising”.

Like many colonized countries on the continent, the colonization of Zimbabwe happened through a web of deceit and violence perpetrated by the British South African Company in the early 1890s. The British South African Company employed a specific method of divide and conquer, or indirect rule, which has been attributed to Fredrick Lugard.

The indirect rule sought to outlaw spirit mediums and rely solely on traditional rulers to help establish colonial authority within colonies. The system employed local chiefs to serve as ‘mouthpieces’ and ‘right hands’ (Fields, 1985), on behalf of colonizers who sought to control the chiefs for the ultimate aim of controlling the people. However, the colonizers failed to consider the fact that across many African societies, there isn’t typically a separation between the political, social and religious aspects of life and this meant that spirit mediums, known as n’angas, were just as powerful and influential as traditional chiefs (Kaoma, 2016).

To establish the dominion of chiefs over their localities, the colonizers outlawed n’angas and this set the stage for the influential roles spirit mediums played during what is now known as the First Chimurenga. According to Kaoma (2016), the attempt to outlaw spirit mediums and to denounce witchcraft and superstitions also created a social crisis which resulted in an undermining of the authority of chiefs whom themselves depended on spirit mediums for their authority.

Expulsion from their ancestral lands and imposed taxes further compounded the grievances that the Shona and Ndebele had against their colonizers. So, between 1896 and 1897, the Shona and the Ndebele communities, through the help of n’angas, violently rebelled against the British South African Company.

The rebellion was led by spirit mediums who were adherents of the Mwari Deity or ancestral cult. The mediums who communicated with Mawri and channelled the deity’s messages to the community were mainly women and Kaoma (2016) emphasized the fact that Mwari’s voice was a woman to highlight the important role women played within the belief system as well as the resistance movement.

The deity Mawri is quoted as attributing various misfortunes including severe drought, a locust invasion, disease in cattle and violent deaths to the arrival of colonizers. The deity thus called for the Shona and Ndebele people to “go and kill these white people and drive them out of our father’s land and I Mwari will take away the cattle disease and the locusts and send you rain.” (Daneel 1970, as cited in Kaoma, 2016).

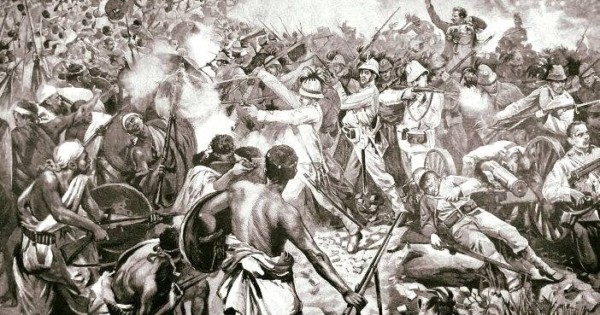

With that, the spiritual leader, known as Mlimo, led nearly 2,000 warriors to fight against the British. It is said that the power of the Ndebele warriors peaked during the full moon and with that knowledge, their first attack was carried out on the night of March 29, 1896, beneath a full moon.

Eventually, the leaders of the rebellion were conquered and sentenced to death by the British, however, they were evoked by nationalist leaders and adherents of the Mawri deity to mobilize support for the Second Chimurenga which eventually led to the independence of Zimbabwe in 1980 (Kamao, 2016).

The Majimaji War (Tanzania, 1904-1908)

The Majimaji War saw Tanzanians rise in resistance against colonization by Germany. Leaving an estimated 100 to 300,000 southern Tanzanians dead, it has been described as one of the most catastrophic wars of colonial Africa (Rushohora, 2019). Like in Zimbabwe a decade earlier, the Majimaji resistance was initiated by a spirit medium named Kinjekitile Ngwale. The resistance was a result of frustration with years of German colonization which featured forced labor, torture, and unfair tax systems.

Ngwale, described as being possessed by a snake spirit called Hongo, was able to mobilize various groups to take part in the uprising. He was a powerful medicine man who gained popularity in the years leading up to the war. As word spread about him, people began traveling to see him as it was widely believed that his medicine provided several benefits including good health and harvest. However, most notably, Nwgale was popular for claiming to have found a way to repel German bullets. His secret was healing water which he referred to as Majimaji, and could “give invulnerability, acting in such a way that enemy bullets would fall from their targets like raindrops from a greased body.”

A study analyzing the coordination of the Majimaji resistance emphasizes the role of “witchcraft” in coalescing various groups of people to struggle against a common enemy (Iliffe, 1967). According to John Iliffe (1967), the group of mediums led by Ngwale were most likely the religious counterparts of the mediums responsible for the Chimerunga Resistance years earlier. However, the mediums in Tanzania were adherents of a serpent deity and were referred to as the Kolelo cult and believed to have possessed supernatural elements including mediumship, possession, and command over death (Iliffe, 1967).

Tanzanian warriors, armed only with arrows, spears, and Majimaji water, thus launched an offensive against the Germans, first attacking small outposts, before spreading throughout the colony. Eventually, the Majimaji War involved 20 different ethnic groups all fighting towards dispelling German colonizers.

The Role of Religion in Modern Resistance Movements

In a modern, increasingly globalized and multicultural world, what role can religion play in resistance movements such as the #EndSARS or #BlackLivesMatter movements?

Nepstad & Williams (2007) argue that religion provides important organizational resources including networks of members, meeting spaces, fund-raising capacities, leadership, and free spaces to promote the development of organizing skills, etc. However, beyond these, religious institutions can also offer theological and ideological critiques of existing social issues such as the wanton killings and brutalization of people by agents of the state. Even within multicultural societies where there might be an absence of a unifying ‘Cultural Religion’ (the overlap between cultural and religious elements (Nepstad & Williams, 2007), extant religious institutions can still render themselves useful to modern resistance movements.

However, whether or not existing religious institutions are willing to lend their voices to resistance movements is another area of inquiry entirely. If the response of religious institutions in Nigeria to the #EndSARS movement is any indication, then it can safely be concluded that religious institutions, or at least those in Nigeria, cannot be expected to fully and outrightly support resistance movements. This conclusion is largely drawn from the loud silence that has emanated out of the pulpits of some of the world’s largest megachurches based in Nigeria.

Asides from mega-pastors and churches, other religious entities have also been largely mute during the #EndSARS movement. The Association of Nigerian Witches and Wizards, known to have declared its support in 2014 during the fight against Boko Haram, has largely been quiet. So has the Muslim religious body in Nigeria.

So What?

As seen with the Chimurenga and Majimaji movements, a shared cultural religion was pivotal in bringing together different groups which collectively participated in both movements. However, and perhaps, largely due to the suppression of African religions, we are likely never to see a similar uprising as either the Chimurenga or the Majimaji which were both entirely inspired and dependent on various aspects of the prevailing African belief systems.

Still, there are various concepts from African religions that can inspire modern resistance movements, after all, as John Mbiti has asserted, Africans’ belief in God has always engendered a moral response which has directed moral life and interaction long before the first European settlers came with their religions and philosophies.

Sources

- Beverton, A. (2009, June 21). Maji Maji Uprising (1905-1907). https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/maji-maji-uprising-1905-1907/#:~:text=A%20prophet%E2%80%94Kinjikitile%20Ngwale%E2%80%94emerged,against%20the%20Germans%2C%20attacking%20atBritish

- Broadcasting Corporation. (n.d.). The Story Of Africa| BBC World Service. Retrieved October 28, 2020, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/africa/features/storyofafrica/11chapter7.shtml

- Emory University. (2016). The Maji Maji Rebellion | Violence In Twentieth Century Africa. https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/violenceinafrica/sample-page/the-maji-maji-rebellion-2/

- Hay, M. (2014, October 28). The Association Of Nigerian Witches And Wizards Is Helping To Fight Boko Haram. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/5gkqnn/the-association-of-nigerian-witches-and-wizards-is-a-thing-and-they-are-helping-fight-boko-haram

- Ikechukwu, P. (2019, February 21). The Essence Of African Traditional Religion. Church Life Journal. https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/the-essence-of-african-traditional-religion/

- Iliffe, J. (1967). The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion. J. Afr. Hist., 8(3), 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853700007982

- Nepstad, S. E., & Williams, R. H. (2007). Religion in Rebellion, Resistance, and Social Movements. In J. A. Beckford & N. J. Demerath III (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. SAGE. https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/hdbk_socreligion

- Rushohora, N. A. (2019). Facts and Fictions of the Majimaji War Graves in Southern Tanzania. Afr Archaeol Rev, 36(1), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-019-09324-2