I have lived in Europe for a little over a year now. The experience has felt like a personal social experiment to find a place in the world I belong outside of my ‘natural habitat’ and the lands of my ancestors in the far northwestern state of Kaduna, Nigeria.

As I settle into these Western worlds and attempt to create for myself a place in it, I am continually jarred by what I can only describe as a prevailing disconnection between the human and their soul. This is not necessarily a new phenomenon that I have observed. The case is also largely true for many people in the country I come from. In Nigeria, I met, loved, cared for, and even worked with people whose detachment from their spirits was glaring in how they treated themselves and responded to the world around them.

Having lived here now for a over year, I am observing that the major difference between the human-soul separation in the West and my ancestral lands is the fact that this separation from spirit has gone on for much longer and has thus happened so extensively that it feels almost hopeless that there may be redemption for the populations in these parts of the world.

In my home country, I see that this separation is happening quite gradually and it makes me fear for the future of my country, and the people I love who are still there. It makes me wonder if there will ever be a safe way back home, to the heart and soul of what it originally meant to know ourselves and perceive each other as powerful spirits who have incarnated here on Earth for a collective human experience.

A buzzword I have come to have a love-hate relationship with is “decolonization.” Everybody and their grandmama wants to decolonize something. I am not even going to play innocent, I have been on the decolonization bandwagon for years now and this is evident in at least three well-funded projects I have been a part of. What has however remained a jarring experience is that many people I have come across who are on this decolonization train, that is headed only god knows where, are still very much colonized in their thinking and how they relate to the world around them.

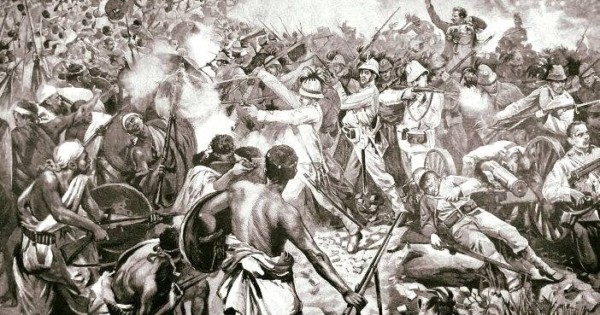

Now, I will be the first to make excuses for people because most of us alive today have been socialized in a colonized world. Many of us know nothing of a world before colonization and that is not necessarily of our own making. However, after being a part of the conversation now for some time, and having questioned my intentions, beliefs, and actions, I have come to see that decolonization is nothing more than a buzzword that gets people and institutions a certain kind of attention and access when they need it. Worse, the actions of many agents and institutions that seem to center this idea of decolonization are, in fact, a sort of neo-colonization of already colonized populations and cultures.

This is dangerous territory because these people and institutions are only interested in specific aspects of the culture and lives of already subjugated people that fit a certain narrative and agenda. These folks are not interested in the sovereignty of previously colonized cultures or even restoring colonized peoples and cultures to their former glory. For them, ‘decolonization’ is a cool word to throw around to show that they are aware of the evils of colonialism, and possibly that they also believe in the autonomy of the colonized. However, when one attempts to engage deeper in the discourse on decolonization, beyond the niche area that has been chosen as the main lens through which we can engage in the discourse, one begins to find various gaps in the knowledge, understanding, and even interest of what it truly means to decolonize.

As a spiritual practitioner and a person who leads and lives spirit-first, quite like my pre-colonial ancestors did, I have come to find the discourse on decolonization to be shallow, lacking in spirit and thus substance. Furthermore, this emphasis on decolonizing still centers the ‘colonial’, and that simply rubs me the wrong way.

I love a good inquiry, questions have led me down the path of many a life-changing realization and revelation. So, my question to everyone, and no one at all, is this:

When you use the word ‘decolonize’ what are you attempting to say or do?

Do your ‘decolonization’ efforts only begin and end when a project is proposed, planned, and implemented, or are you working also on decolonizing your mind, beliefs, and the structural systems that prevail?

I simply am unable to see beyond the fact that this word continues to center a system of oppression many of us claim we do not want. I wonder what alternative words and nomenclature exist for our collective and individual efforts to return to a place before the horrors of colonialism separated us from our individual and collective human spirits.

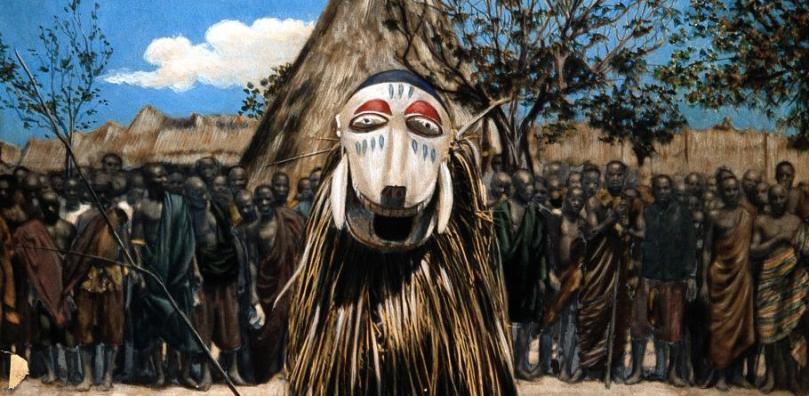

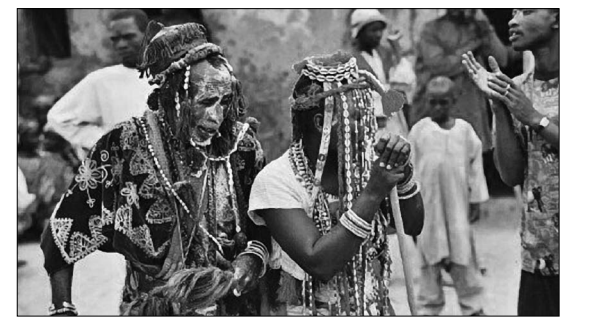

Speaking of spirits, people want to talk about decolonization and yet are deathly afraid of admitting that they are spirit beings having a human experience. There is no Indigenous culture on Earth that does not allude to humans having a spirit or the fact that we are, by existing, in a relationship with a higher realm beyond this physical and material existence. Yet, I continue to meet people who want to decolonize the world and cannot even fathom this crucial aspect of Indigenous life.

It makes me wonder, if we cannot understand and reconcile this crucial separation that has happened between spirit and matter, what exactly are we then trying to decolonize? If these so-called decolonial efforts are not leading back to a union between spirit and matter, what exactly are we fighting for?

It is laughable at best, and at worst, we are witnessing the coopting of Indigenous knowledge and wisdom in a similar way that colonizers took land, resources, and anything else of value they could lay their hands on after they encountered Indigenous folks. The people and institutions pushing for decolonization without first doing an internal soul-search of how their actions and systems maintain a colonized structure are simply paying lip service and are thus not different from the colonizers who pillaged Indigenous cultures.

The way I see it, this is what it comes down to: are we truly interested in restoring Indigenous systems where people lived in communion with the Great Spirit, the Earth, and each other, or are we simply interested in surviving and getting by in these post and neo-colonial worlds?