Previously, we discussed animism as a worldview that regards every aspect of nature as imbued with, and therefore an extension of, Spirit. This perspective fosters a profound respect for and connection with nature, as seen across diverse animistic traditions worldwide. Building upon that foundation, this piece elaborates on the central belief that nature, as an extension of Spirit, is sacred. It also examines the resulting sense of ecological responsibility—expressed through reciprocity and ritual—that enabled indigenous cultures to thrive in harmony with nature prior to Western imperialism.

The Separation Myth: Nature as Commodity

Life in 2025 is characterized by ongoing confrontations with a range of crises that, although distinct in time and place, collectively signal a profound disconnection between humanity and its spiritual essence. Western imperialism, as a systemic force, has permeated virtually every facet of global society. Today, numerous genocides—widely covered by the media but insufficiently challenged by the international community—serve as stark illustrations of a system that devalues the sanctity of life. Within this paradigm, all life is commodified for profit, and the loss of innocent lives is regarded as an acceptable cost in the relentless pursuit of resources.

Recent mass killings in regions such as Gaza, Sudan, and the Congo are often linked to the exploitation of natural resources by imperialist forces. To facilitate resource extraction, these entities frequently seek to suppress resistance from local populations, who are often indigenous to these areas. As a result, the environment itself becomes central to the broader context of violence and conflict. The large-scale attacks witnessed today reflect a continuation of historical tactics employed by imperial powers against indigenous populations that resisted their operations.

Over time, Western imperialism has continually refined its justifications for dominance. Initially, expansion was framed as the divine right of monarchs. Before that, Christian missionaries felt compelled to spread their faith worldwide. Unfortunately, colonial expansion frequently followed missionary activity, converting colonies into sites for resource extraction by European powers. Consequently, contemporary global power structures are a reflection of the disparities established during the colonial era. While former colonies may no longer be directly exploited for their land and resources, they still experience significant indirect consequences. Today’s global politics constitute a competitive arena in which powerful nations vie for control over land, resources, and markets. Within Western economic frameworks, these resources are considered scarce, and the ongoing struggle for them has perpetuated and intensified imperialistic practices.

Sankofa: Reconnecting with the Spiritual Essence of Nature

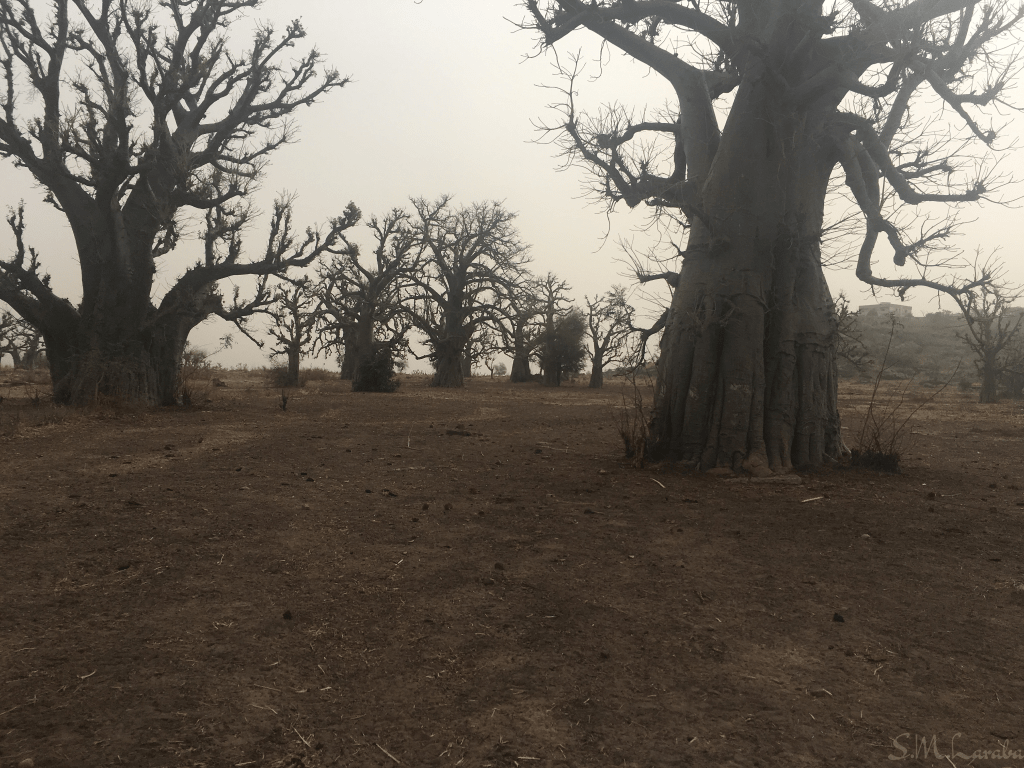

Long before the concept of the divine right of kings emerged and before missionaries arrived in indigenous lands, animistic cultures around the world—despite differences in belief—shared a central principle: profound reverence for nature. In these traditions, the Cartesian distinction between Spirit and matter does not exist. Indigenous peoples view themselves as integral to nature, not separate from it. For them, every aspect of life that is not human-made is regarded as an extension of God or Spirit. As Godwin Sogolo (1993) notes, “To the African [Indigenous] mind, reality is one unified whole. What happens to one part of creation reverberates through the entire system.”

The concept of interconnectedness is central to animistic beliefs and, over centuries, has fostered a sense of duty and stewardship for nature within indigenous cultures. Trees, forests, rivers, animals, and soils are not merely resources to be exploited; instead, they are recognized as essential components of the cosmos, imbued with Spirit, and thus regarded as sacred. Unfortunately, colonial missionaries—often agents of imperial expansion—dismissed these beliefs as superstition or, at times, labeled them as witchcraft. As a result, animism and its sophisticated ecological philosophy have largely faded from collective human consciousness (Kimmerle, 2006; Gumo et al., 2012). Now, at a pivotal moment in history, when the consequences of this loss are increasingly apparent, humanity must confront its past and reclaim the sacred knowledge that once enabled harmonious coexistence with the natural world.

The wisdom embedded in animistic practices is extensive. In recent years, modern science and Western academic thought have begun to incorporate animistic principles, particularly in fields such as spiritual ecology, ecofeminism, and environmental conservation. Scholars, theologians, and conservationists increasingly turn to animism as both a philosophical framework and a relational approach to engaging with the natural world—an orientation that may prove vital to humanity’s survival. Distinct aspects of animistic thought and humanity’s relationship with nature have generated significant interest among Western thinkers.

Reciprocity as an Animistic Principle

Reciprocity stands as a fundamental principle in animistic traditions. In “Ontology and Ethics in Cree Hunting,” Colin Scott (2014) explains that, among the Cree—especially hunters who engage with wild animals—reciprocity is rooted in respect. Although the meaning of respect may shift depending on the context and entities involved, it consistently serves as the ethical foundation for all relationships. Scott frames “respectful reciprocity” as the approved way of relating not only between hunters and animals but also between humans and the natural world as a whole.

The importance of reciprocity is deeply embedded in animistic cultures and is manifested in various forms. In Cree mythology, for instance, this idea is woven through cosmological narratives, illustrating how humans received culture, fire, language, and tools from animals who originally possessed them. Scott’s observations of the relationship between Cree hunters and the animals they pursue exemplify how animistic cultures perceive their connection to non-human nature as one of gift exchange (Adloff, 2025). Indigenous animistic traditions emphasize drawing resources from nature while simultaneously giving back, fostering a balanced and enduring exchange between humans and the natural world. These societies demonstrate profound respect for nature and honor the sacred partnerships formed through reciprocal exchanges in hunting and sustenance.

Adloff (2025) asserts that in cultures maintaining reciprocal relationships with nature, the notion of human superiority is inconceivable. Instead, these societies emphasize gratitude for nature’s gifts, recognizing that both humans and nature are components of a unified whole. As Sogolo (1993) notes, ‘what happens to one part of creation reverberates through the entire system.’ The resources offered by nature and the stewardship provided by humans circulate in a continuous cycle that sustains all life. Ultimately, indigenous societies flourish by acknowledging nature’s abundance and reciprocating through responsible care and stewardship of the environment.

The Role of Rituals in Honoring Nature

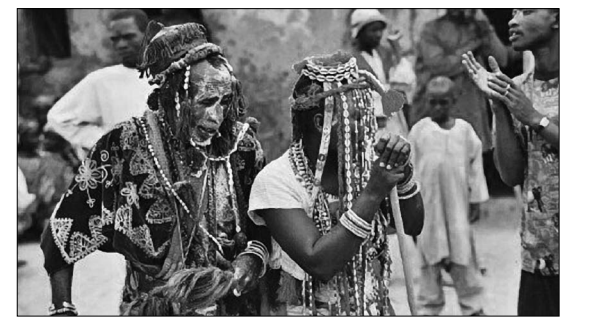

Within indigenous cultures, rituals are essential for nurturing, preserving, and honoring the connection to the divine and the spirit world. In “Ritual: Power, Healing and Community,” Elder Somé (1993) underscores the significance of rituals, observing that “the abandonment of ritual can be devastating.” He further asserts, “from a spiritual standpoint, ritual is inevitable and necessary if one is to live.” Recognizing this sacred imperative, indigenous societies have formalized their commitment to the Earth through diverse rituals and celebrations that honor the natural world.

In Nigeria, the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove holds profound importance for the Yoruba people as a site dedicated to the river goddess Osun, who is revered for bestowing fertility, healing, and protection. Annually, the Osun-Osogbo festival draws thousands of Ifa practitioners from around the globe. This multi-day celebration features singing, dancing, prayers, and offerings, honoring a centuries-old covenant between the community and the river. Similarly, rainmaking rituals are prevalent among the Shona people of Zimbabwe. During periods of drought, the Shona convene at sacred hills and riverbanks to invoke ancestral spirits for rain. These ceremonies include millet beer, livestock offerings, and ritual songs, reflecting the belief that rainfall is not guaranteed but is a blessing contingent upon maintaining a harmonious relationship with the land and Spirit.

Even before the spread of Christianity across Europe, indigenous European societies had honored nature through various rituals. The Celts, for example, regarded oak groves and wells as sacred spaces where Druids mediated between humans and the unseen world. Offerings—such as jewelry or weapons—were placed in rivers and lakes as gifts to the deities and spirits believed to inhabit those waters. In Northern Europe, Norse communities revered Yggdrasil, the cosmic tree linking heaven, Earth, and the underworld. At sacred groves and springs, sacrifices were performed to ensure fertility, protection, and balance.

Indigenous cultures across Africa, Europe, and beyond demonstrate deep respect for nature through both personal and communal rituals. These practices extend beyond mere symbolism; they represent continuous, intentional engagement with the natural world and reflect a foundational belief in the interconnectedness and interdependence of all existence. Whether in the groves of Osogbo, the sacred wells of the Celts, or the rain shrines of Zimbabwe, indigenous societies have historically honored nature through ritual. As Mbiti (1969) states, “The physical and the spiritual are but two dimensions of the same universe; ritual ensures they remain in harmony.”

Reclaiming Animism in Contemporary Society

The renewed interest in animism among modern scientists and within Western academic discourse parallels a global revival of animistic practices. In the West, there is a notable resurgence among members of the African diaspora seeking to reconnect with their ancestral heritage, which is inherently animistic and grounded in the recognition of, and respect for, the Spirit that unites humanity and nature. These movements are instrumental in healing the wounds of colonial disruption by fostering spiritual kinship, which, in turn, informs more sustainable ecological practices (Gumo et al., 2012). Similarly, eco-activist Wangari Maathai, founder of the Green Belt Movement, drew profoundly on ancestral reverence for trees as she mobilized women to plant millions across Kenya. Maathai described planting “seeds of peace and hope,” grounded in the belief that humanity cannot achieve peace on an endangered planet.

Animism, as expressed through diverse indigenous cultures worldwide, offers a compelling alternative to Western ecological paradigms. Animistic beliefs approach the Earth as kin rather than as a resource to be exploited. From this vantage point, the crises currently facing our planet—including environmental and climate challenges—are not merely surface-level issues, but manifestations of a profoundly fractured relationship between humanity and Spirit, the essential thread binding us to nature and all living beings.

In conclusion, reengaging with animistic worldviews invites us to reconsider our relationship with the natural world—not as detached observers or exploiters, but as participants in the dynamic and interconnected web of life. By acknowledging the wisdom embedded in indigenous traditions and embracing a sense of reciprocity, respect, and spiritual kinship with nature, we can foster more sustainable and harmonious ways of living. As global challenges intensify, adopting these perspectives offers a hopeful path toward spiritual and, ultimately, ecological restoration for a more balanced and compassionate future for both humanity and the planet.

References

- Chirikure, S., Nyamushosho, R., Chimhundu, H., Dandara, C., Pamburai, H., & Manyanga, M. (2017). Concept and knowledge revision in the post-colony: Mukwerera, the practice of asking for rain amongst the Shona of southern Africa.

- Feiler, B. (2014) Sacred Journeys With Bruce Feiler | Osun-Osogbo, PBS.org. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/sacredjourneys/content/osun-osogbo/ (Accessed: September 10, 2025).

- Gumo, S., Gisege, S. O., Raballah, E., & Ouma, C. (2012). Communicating African Spirituality through Ecology: Challenges and Prospects for the 21st Century. Religions, 3(2), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel3020523

- O’Driscoll, D. 2022. “Introduction To Animism: Definitions And Core Practices For Nature Spirituality – The Druids Garden.” The Druids Garden – Spiritual Journeys In Tending The Living Earth, Permaculture, And Nature-Inspired Arts. July 14, 2022. https://thedruidsgarden.com/2022/07/14/introduction-to-animism-definitions-and-core-practices-for-nature-spirituality/.

- Scott, C. 2014. Ontology and Ethics in Cree Hunting: Animism, Totemism and Practical Knowledge. Edited by Graham Harvey. London: Routledge.

- Sogolo, G. (1993). Foundations of African Philosophy: A Definitive Analysis of Conceptual Issues in African Thought. Ibadan, Nigeria: Ibadan University Press

- Somé, M. P. (1997). Ritual: Power, healing, and community. Penguin.

- Taylor, B. (2013) ‘Kenya’s Green Belt Movement Contributions, Conflict, Contradictions, And Complications In A Prominent Environmental Non-Governmental Organization (Engo)’, in Trägårdh, L., Witoszek, N., and Taylor, B. (eds) Civil Society in the Age of Monitory Democracy. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 181–207. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1515/9780857457578 (Accessed: September 10, 2025).